Lace is see-through openwork or mesh-work made with linen, cotton, silk or synthetic threads, and it can be crafted by hand using the techniques of embroidery, stitching, knitting, crocheting and weaving with bobbins, a needle, shuttle or a crochet hook, or made by machine. The origins of lacemaking can be traced to entirely practical purposes; they first started as a way to finish or border fabric to prevent the woven weft from unravelling. Embroidery as a skill peaked in the Renaissance in monasteries (decoration of ecclesiastical textiles) and at courts, and in the 17th century also in the urban setting. Filigree embroidery quickly spread across Europe and when it reached Holland, or more exactly Flanders, where thinner cloth was being weaved, the thinner yarn gave rise to the birth of bobbin lace. Lacemaking techniques can also be named after their place of origin (e.g. Venetian, Valenciennes, Idrija lace and so on.). At the height of the Renaissance, some lace evolved into a stand-alone product that was independent of fabric.

Renaissance bobbin and needle lace was made with strict geometrical designs and it was an extremely popular trimming for clothes worn by the urban middle class, such as starched high collars or cuffs. During the Baroque period, the strict geometrical designs slowly disappeared and soon after, so did the border points. Lace became increasingly independent, with a single key motif which most often depicted a luxuriant floral bouquet. Italian and French needle lace closely resembled Flemish and Belgian bobbin lace, and they were hard to distinguish. Fashionable lace flooded France in the 17th century, and the extraordinary demand for lace led to the establishment of the Royal Lace Manufacture in Alençon in 1660. More broadly, lace was reaching an exceptional level of quality all over Europe and becoming a precious trade and export commodity. The Rococo saw a trend of increasingly fine patterns and miniature motifs; very fashionable elements included garlands and other plant patterns, whereas large ornaments and reliefs were in decline. In the time of Napoleon, calmer and more simplified forms began to emerge in the Empire style, which was dominated by small bouquets, delicate blossoms and translucent nets with small dots, while borders were increasingly made without any points. This was also the time when Napoleon mandated that formal attire must be embellished with lace.

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries lace was typically made by hand, mostly from cotton yarn, but not before 1830. Up to that point all lace had been made from linen yarn only. However, in the early 19th century, machine-made lace gradually took over. It began with the machine manufacture of thin and translucent wool or silk mesh fabric – tulle, which encouraged the application of needle and bobbin lace.

The lace housed in the textile collection of the Koper Regional Museum is made in a variety of techniques; handmade bobbin, needle, crocheted, filet lace and mixed lace, combining different types of lace, e.g. needle lace with bobbin lace, and machine-made lace.

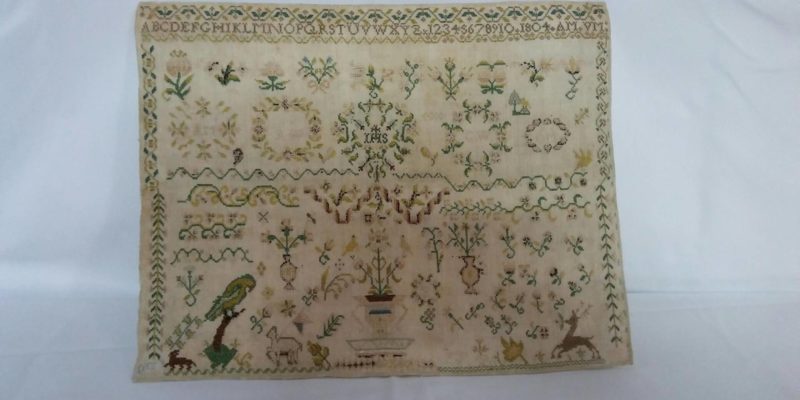

Embroidery is handmade needlework decoration of fabric using silk, cotton, linen or wool thread. Embroidery can be complemented with appliqués or ornamental elements such as transparent or coloured glass beads, sequins, golden or silver metal threads and silk threads. In the Middle Ages, the precious materials and precision of workmanship lent embroidery a special status which was only attainable for religious and secular dignitaries and rulers. Embroidery was mostly the work of nuns until the Late Middle Ages, when embroidery guilds began to form, and it also became a prestigious pursuit among noblewomen. In the 17th century, embroidery began to enhance secular clothing as well, first among the nobility and then well-to-do townspeople. A little later, it was extended to the textile furnishings of noble and middle-class homes. With the introduction of the school system in 1869, embroidery along with other handicrafts became a mandatory part of the school programme for girls from all social classes. Every girl was required to embroider various stitches and a series of motifs on a special piece of material called a sampler. Its obligatory elements included the alphabet, numbers from one to ten, the year it was made and the embroiderer’s monogram. The type of embroidery can be recognised by the technique:

- by counted threads, which meant embroidering with cross stitches, pattern darning, ajours, drawn-thread work and tapestry stitches on open-weave fabric.

- by the pattern, where embroidery was made using the backstitch, the tent, stem and chain stitches, and knots, cutwork and appliqués. They used fabrics with a finer textile weave.

In Istria and Trieste, the prettiest embroidery adorned women’s shawls, covering the chest (peča), which were part of both the daily and festive costume. Embroidery also became a popular pastime of farmers’ wives, who embroidered for the home, and unmarried girls, who used it in preparing their trousseau.