The Italian population never actually accepted the new post-war authorities as their own, nor did they wish to be annexed to Yugoslavia. To begin with, the new authorities made every effort to gain the support of the Italian population of Istria: appealing to the working class with a vision of a better life in the new socialist state, devoting particular attention to the supply of provisions to towns, ensuring consistent application of bilingualism and equal representation on administrative bodies, and so on. Nevertheless, both objective and subjective circumstances meant that the new authorities never gained the broad support of the Italian population. Not even immediately after the war, when the ties between Slovenes and Italians were at their strongest, because of the common struggle against Fascism, and even less so in the years that followed, when conditions changed significantly. The differences between the underdeveloped Slovene hinterland and the Italian-inhabited towns of the Istrian coast were too great for the Italians to accept the idea of Slovenes holding power over them. The authorities did, however, receive some support: in part as a result of class consciousness (the working-class inhabitants of Izola) and in part for reasons of personal advantage (those holding land under the colonisation system). Part of the Italian population openly opposed the new authorities, while the majority were passive as they awaited a decision on the fate of this territory. The circumstances and incidents that caused most mistrust in the new authorities were these: the Morgan Line between the two zones had made commerce with Trieste more difficult, as had the introduction of a new currency (the “jugolira” in 1945 and the Yugoslav dinar in 1949); permanent unemployment, which further increased with the dismantling and removal of factory machinery and fishing boats; the fact that Istria had almost no political or expert cadres of its own, which meant that these came from elsewhere in the Primorska region and, later, from other parts of Slovenia, but these newcomers did not understand the specific characteristics of the area, a shortcoming that also applied to the Slovene political leadership. As a result, many mistakes were made in terms of attitudes towards the Italians, in some cases according to the principle “Whoever is not with us is against us!” Next came a split between the Slovenes and those Italians who up until now had supported the authorities and cooperated with them. This was caused by the crisis of 1948 which saw Yugoslavia expelled from the Cominform on the orders of the Soviet Union. Faced with the choice of “Tito or Stalin”, the majority of the Italian Communists took Stalin’s side, which led to a split within the Communist Party of the FTT, the trade union organisation and other mass organisations. Then there was the critical year of 1953, when war almost broke out between Italy and Yugoslavia and the border between the two zones was closed.

The result of all these developments in the political and economic spheres, which were further inflamed by anti-Yugoslav propaganda in Trieste, was the mass emigration of the Italian population. From this point on, the authorities focused their efforts on Italians from Trieste and nearby towns, former Partisans who had settled in the Istrian district, and those who had immigrated to the Koper district from Croatian Istria and Rijeka, in other words from the area that had already been part of Yugoslavia since 1947.

Piran, 1 May 1945 – celebration of the liberation and International Workers’ Day. On the balcony, the organisers of the celebration – representatives of the Piran CLN with their president Luigi Viezzoli.

Piran, 1 May 1945 – celebration of the liberation and International Workers’ Day. On the balcony, the organisers of the celebration – representatives of the Piran CLN with their president Luigi Viezzoli.

On 13 December 1945 a large crowd of both nationalities gathered in Piran to pay their respects to schoolteacher Antonio Sema, a popular figure who was among the founders of the Socialist party.

On 13 December 1945 a large crowd of both nationalities gathered in Piran to pay their respects to schoolteacher Antonio Sema, a popular figure who was among the founders of the Socialist party.

On 13 December 1945 a large crowd of both nationalities gathered in Piran to pay their respects to schoolteacher Antonio Sema, a popular figure who was among the founders of the Socialist party.

Education

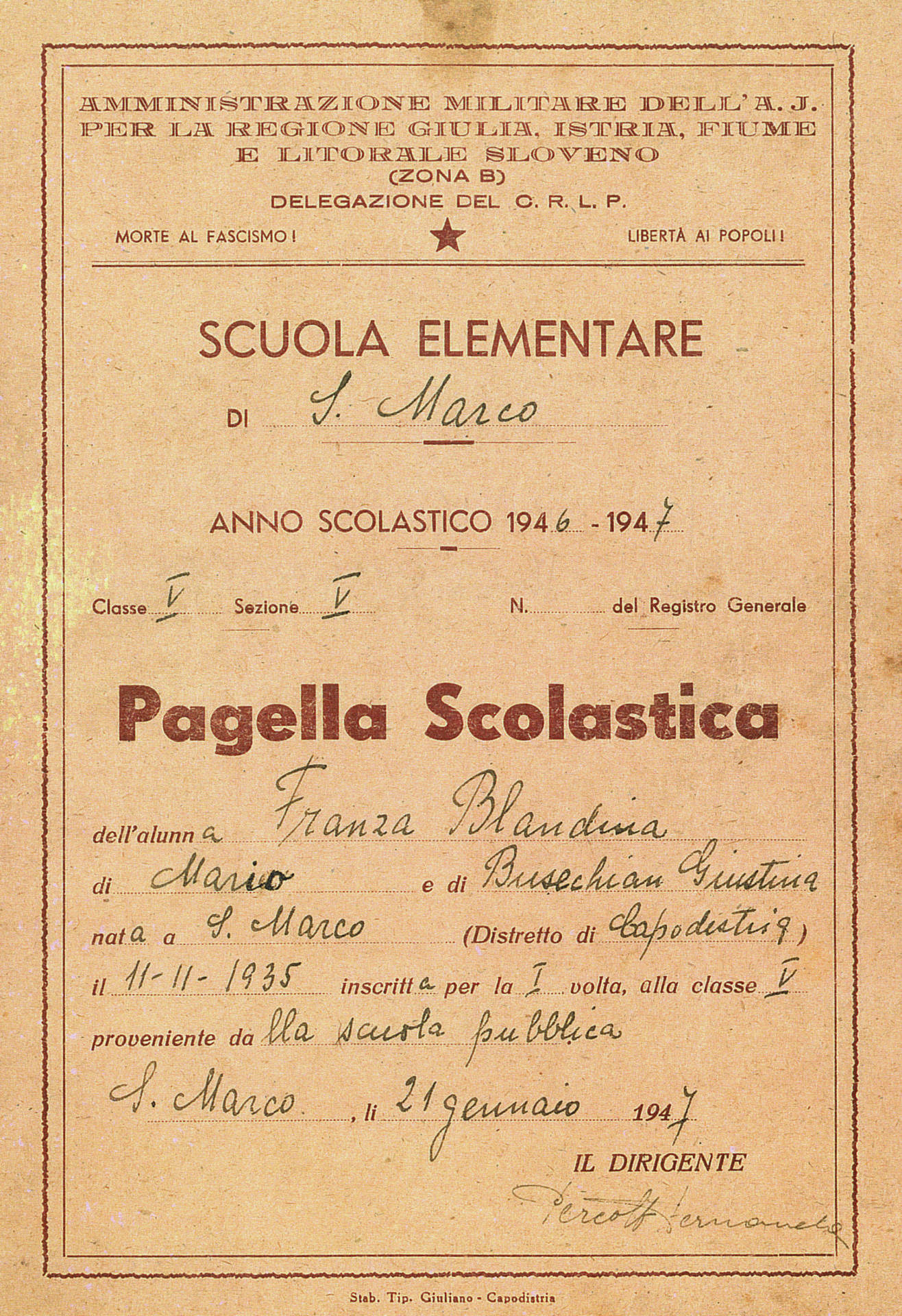

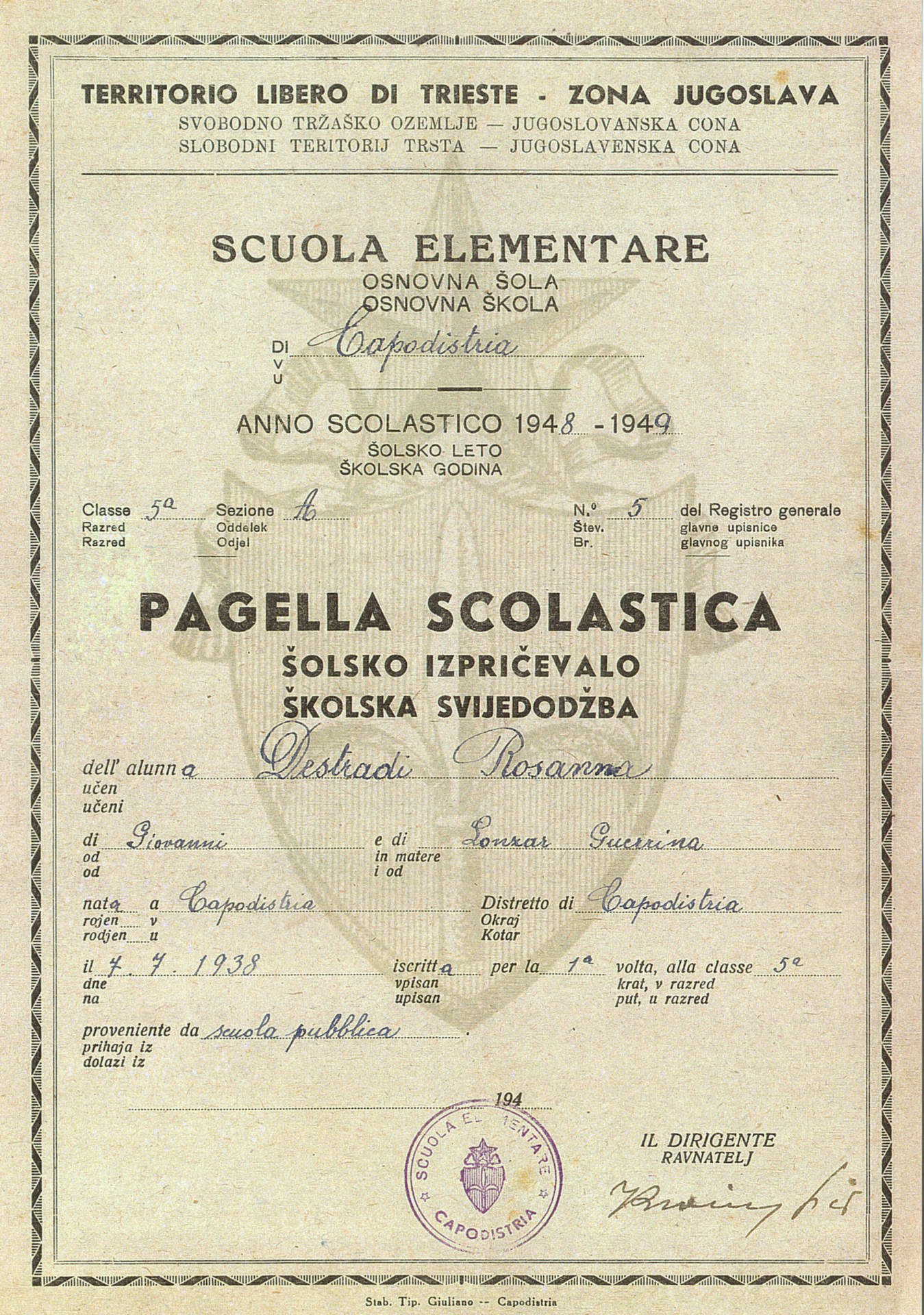

All the primary and secondary schools in the area, with the exception of the nautical academy in Koper and the primary school in Šalara, continued their activity after the war. New schools were opened and, in some cases, classes for Italian students were added in existing Slovene schools. Some closed shortly afterwards, while others began to struggle for existence because of the constantly decreasing numbers of students and teachers.

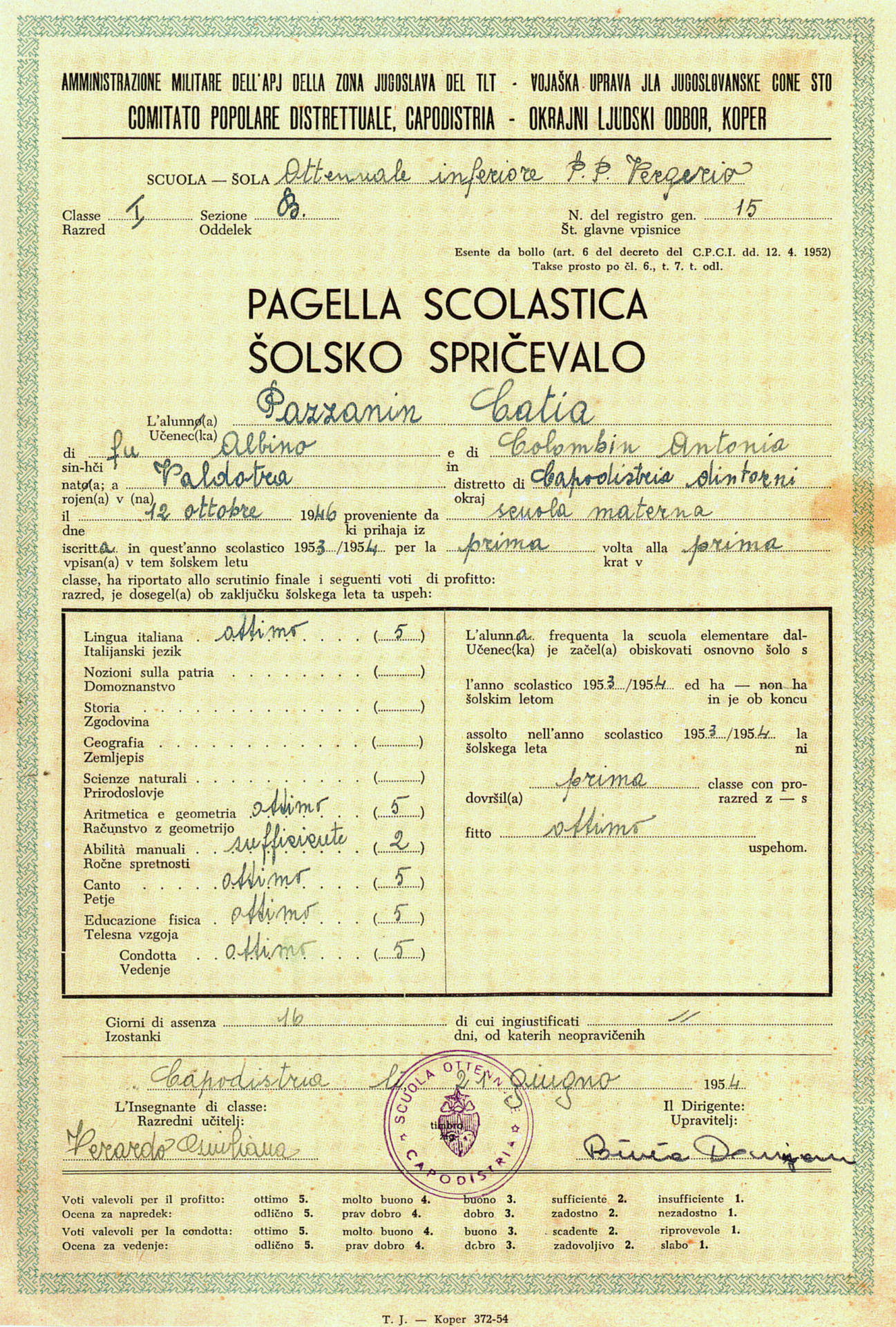

For the first two post-war years, Italian schools maintained the system that was in place in Italy. At the primary level, this meant five classes, while secondary schools were divided into technical institutes and schools of the classical type and included lower secondary and upper secondary levels. The most widespread form of secondary education was the scuola di avviamento professionale (lower vocational school). A general lower secondary education was provided by the scuola media unica, while upper secondary education was represented by the liceo classico. From 1950 onwards, Italian schools were increasingly harmonised with the Slovene education system. With the introduction of the combined eight-year primary and lower secondary school, the scuola media unica and scuola di avviamento professionale were gradually phased out and lower gymnasia reintroduced.

For the most part Italian teachers did not support the current authorities. They were socially passive and in some cases actively opposed the authorities, who considered them adversaries. As a result, many of them abandoned their positions. Some gave official notice but the majority simply stopped coming to work. Their vacated positions were filled by Slovene teachers who had graduated from the Italian teacher training college.

As a consequence of the constant emigration, the number of students also fell from year to year. A further contribution to this decline after 1952 was an ordinance according to which children with a Slav surname were required to attend a Slovene school, even if they did not consider themselves Slovenes. Before this the rule had been that Italian children went to Italian schools and Slovene children to Slovene schools, while children from mixed families went to the school chosen by their parents.

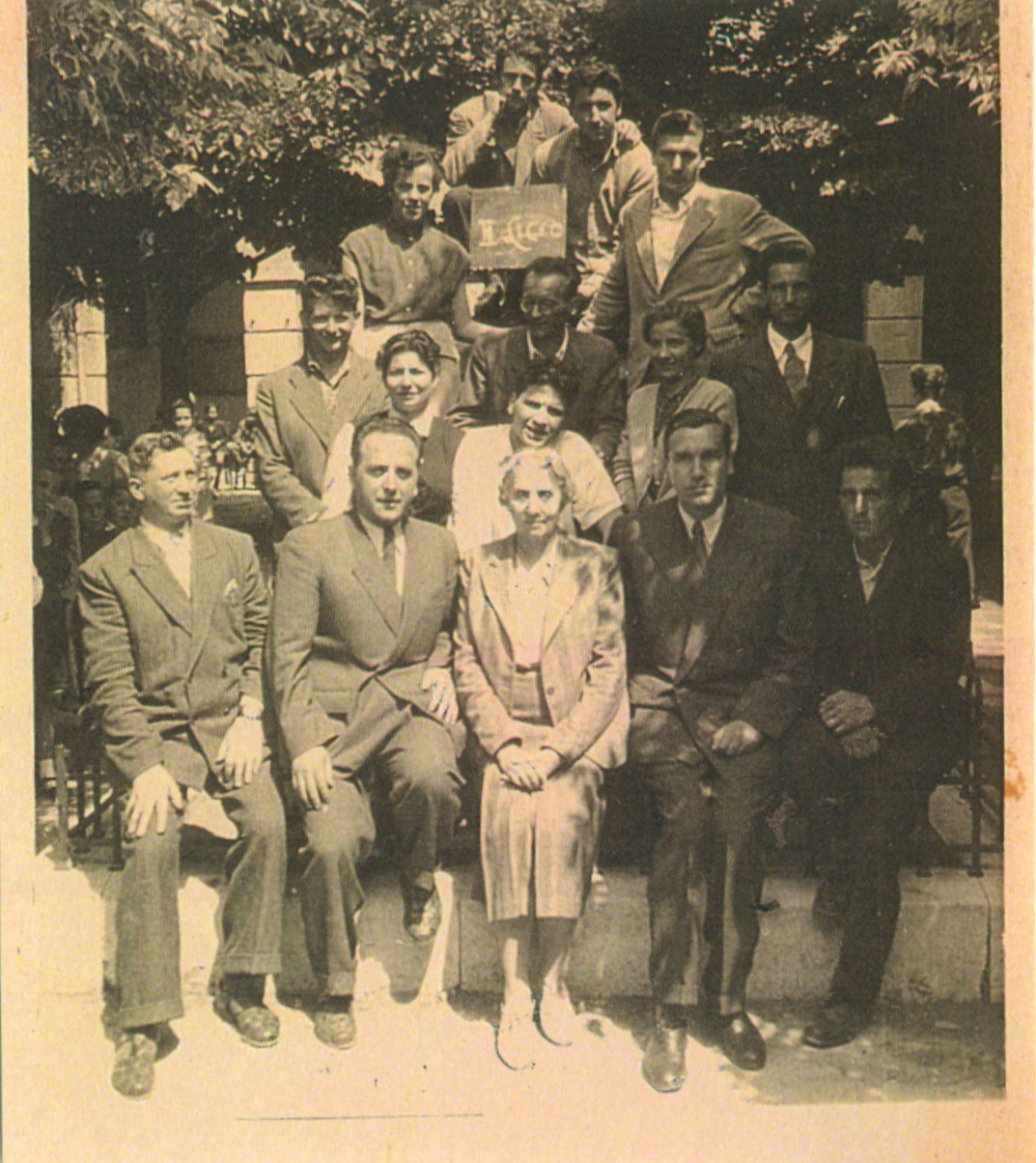

Piran, June 1949 – students of the liceo scientifico with their teachers. In the second row are (standing, from left) Maria Pia Urbani and Dina Petronio and (sitting, from left) Corinna Viezzoli, Guido La Pasquala, Cesare Brumen, Andreina Apollonio, head teacher Paolo Sema, Giorgina Dolce, Tarcisio Benedetti and Oskar Kogoj.

Piran, June 1949 – students of the liceo scientifico with their teachers. In the second row are (standing, from left) Maria Pia Urbani and Dina Petronio and (sitting, from left) Corinna Viezzoli, Guido La Pasquala, Cesare Brumen, Andreina Apollonio, head teacher Paolo Sema, Giorgina Dolce, Tarcisio Benedetti and Oskar Kogoj.

Piran, June 1951.

Piran, June 1951.

Izola, June 1947 – fifth-year primary school pupils with their teacher Felicita Pugliese.

Izola, June 1947 – fifth-year primary school pupils with their teacher Felicita Pugliese.

Koper, June 1954 – students and teachers of the liceo: Vladimir Lenardič is seated third from the left. On his left are Fulvio Tomizza (still a student), Miroslav Žekar, Giovanni Rett, Srečko Vilhar, Clotilde Armandi, Mario Bratina and Jože Pohlen.

Koper, June 1954 – students and teachers of the liceo: Vladimir Lenardič is seated third from the left. On his left are Fulvio Tomizza (still a student), Miroslav Žekar, Giovanni Rett, Srečko Vilhar, Clotilde Armandi, Mario Bratina and Jože Pohlen.

Koper, June 1954 – students of the lower gymnasium with their teachers: L–R Kravar, Jože Pohlen, Luigia de Belli, Lidia Steffè, Don Carlo Musizza, Marjan Žerjal and Ercole Parenzan.

Koper, June 1954 – students of the lower gymnasium with their teachers: L–R Kravar, Jože Pohlen, Luigia de Belli, Lidia Steffè, Don Carlo Musizza, Marjan Žerjal and Ercole Parenzan.

Koper, academic year 1953/54 – students of Class 1b with their teacher Giuliana Verardo in front of the new Slovene-Italian school.

Koper, academic year 1953/54 – students of Class 1b with their teacher Giuliana Verardo in front of the new Slovene-Italian school.

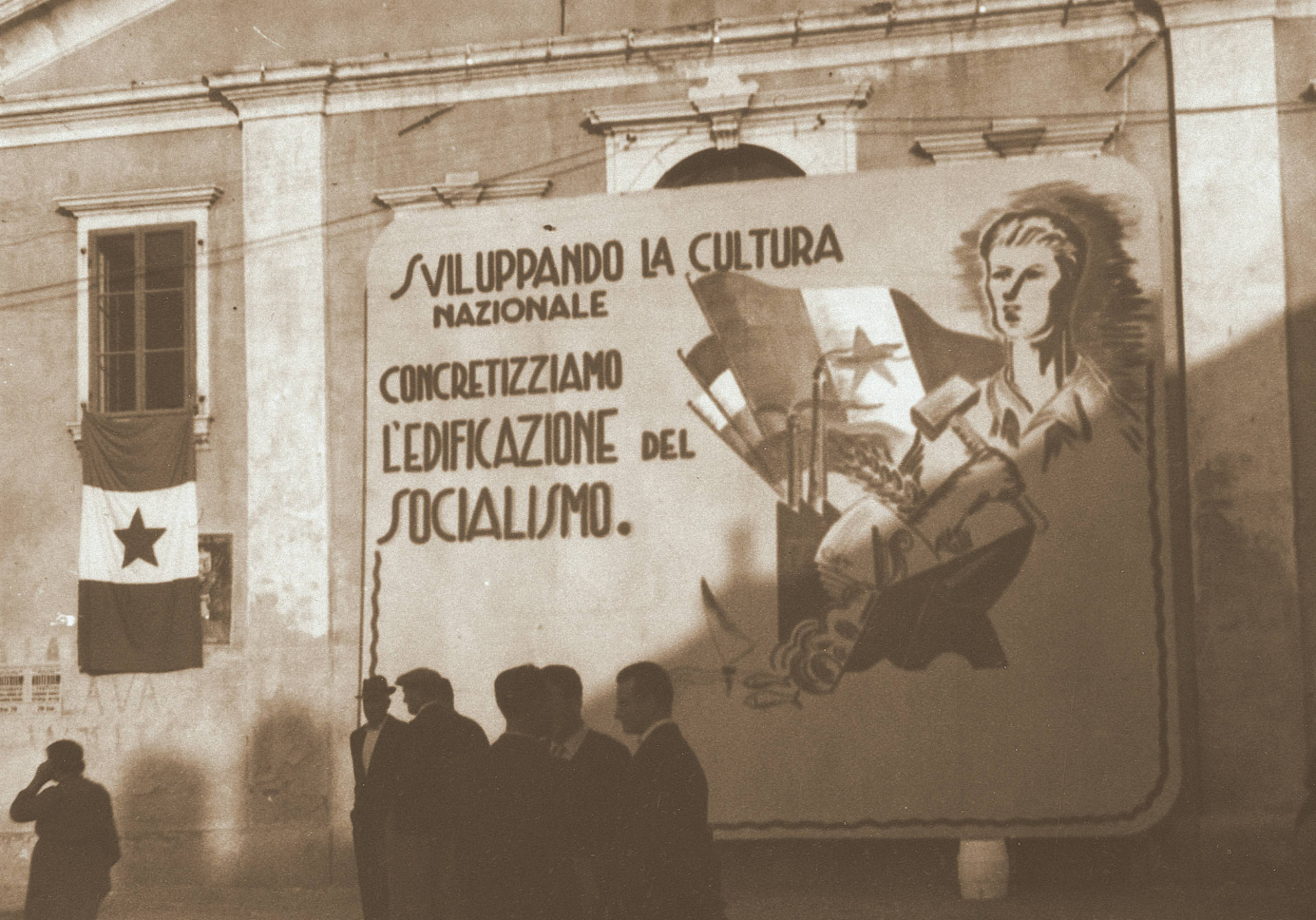

Culture

No sooner had the war ended, than the idea of establishing an artistic and cultural association was raised. The result was the creation of the Ente Cittadino dello Spettacolo (ENCIS) in Koper, an organisation that covered a range of activities (orchestra, choir, drama and ballet). It put on good-quality performances in the hall of the Convent of Santa Chiara (Sveta Klara), which were well attended.

Italian cultural associations operated within the context of the Centro di Cultura Popolare (Centre of Popular Culture), which in 1947 developed a new form of operation, namely Italian cultural circles, which incorporated the existing cultural clubs and societies that were to be found in all but the smallest localities. The activities of these circles were broad and varied, with amateur dramatics being particularly popular.

The next phase of development was the establishment of the Union of Italians of the Istrian District in March 1950, which brought under its roof every aspect of the life of the Italian population with an emphasis on preserving their cultural identity. After the Istrian District was abolished, it divided into the Union of Italians of the Koper District and the Union of the Italians of the Buje District. Following the annexation of Zone B to Yugoslavia, these were incorporated into the Yugoslav minority organisation the Union of Italians of Istria and Fiume (Rijeka).

The Union of the Italians organised an annual review of Italian culture for the whole of Zone B, and also local reviews in individual towns. In 1953 the activity of these circles dwindled greatly as a result of emigration and only began to revive in the spring of 1954, when the departed members were replaced by newly arrived Italians from Croatian Istria and Rijeka.

In 1951 the Teatro del Popolo, a semi-professional Italian theatre company, was established in Koper but only operated for three seasons. It was based in the Koper municipal theatre, which had been renovated in 1949. The company premiered seven productions.

Koper, October 1950 – festival of Italian culture.

Koper, October 1950 – festival of Italian culture.

Izola, 22 October 1950 – festival of Italian culture organised by the Union of Italians of the Istrian District.

Izola, 22 October 1950 – festival of Italian culture organised by the Union of Italians of the Istrian District.

Scene from the play Carmen, staged by the Teatro del Popolo in the 1953/54 season.

Scene from the play Carmen, staged by the Teatro del Popolo in the 1953/54 season.

Teatro del Popolo – scene from the comedy Il fornaretto di Venezia.

Teatro del Popolo – scene from the comedy Il fornaretto di Venezia.

Teatro del Popolo – scene from Goldoni’s comedy The Vengeful Woman.

Teatro del Popolo – scene from Goldoni’s comedy The Vengeful Woman.

Emigration

The exodus from the Koper district began immediately after the end of the war and continued in waves, some bigger than others, until 1957. The first to leave were Fascist sympathisers and members of the intelligentsia who opposed annexation to Yugoslavia. Later on, other classes of the population began to emigrate for economic, political and psychological reasons, including those who had received benefits from the new authorities (those holding land under the colonisation system). Some people emigrated legally, with permits from the Yugoslav military administration, but many left their homes in secret. After 5 October 1954, emigration continued according to the provisions of the London Memorandum, which gave inhabitants of both zones the right to freely choose citizenship. The two criteria were place of domicile and language spoken. Emigrants were permitted to take personal items, furniture, agricultural produce, tools, livestock and means of transport with them, in other words practically all their movable property.

Between 1945 and 5 October 1954 a total of 9,008 people emigrated. Between this date and 1958, a further 16,062 people emigrated, making a total of 25,070 emigrants, of whom slightly more than 19,000 were Italians.

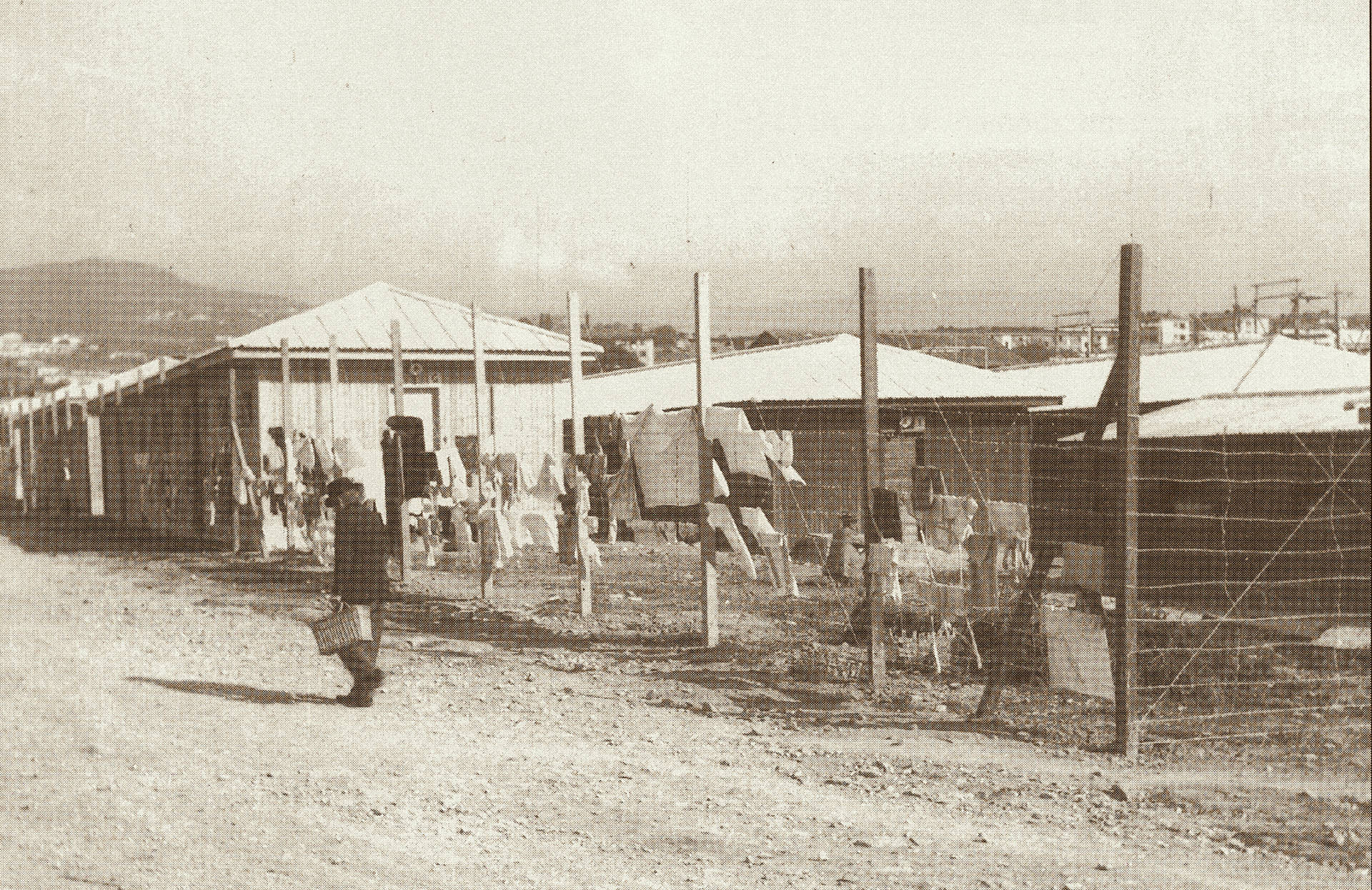

Trieste, 1951 – refugee camp in the San Sabba district.

Trieste, 1951 – refugee camp in the San Sabba district.

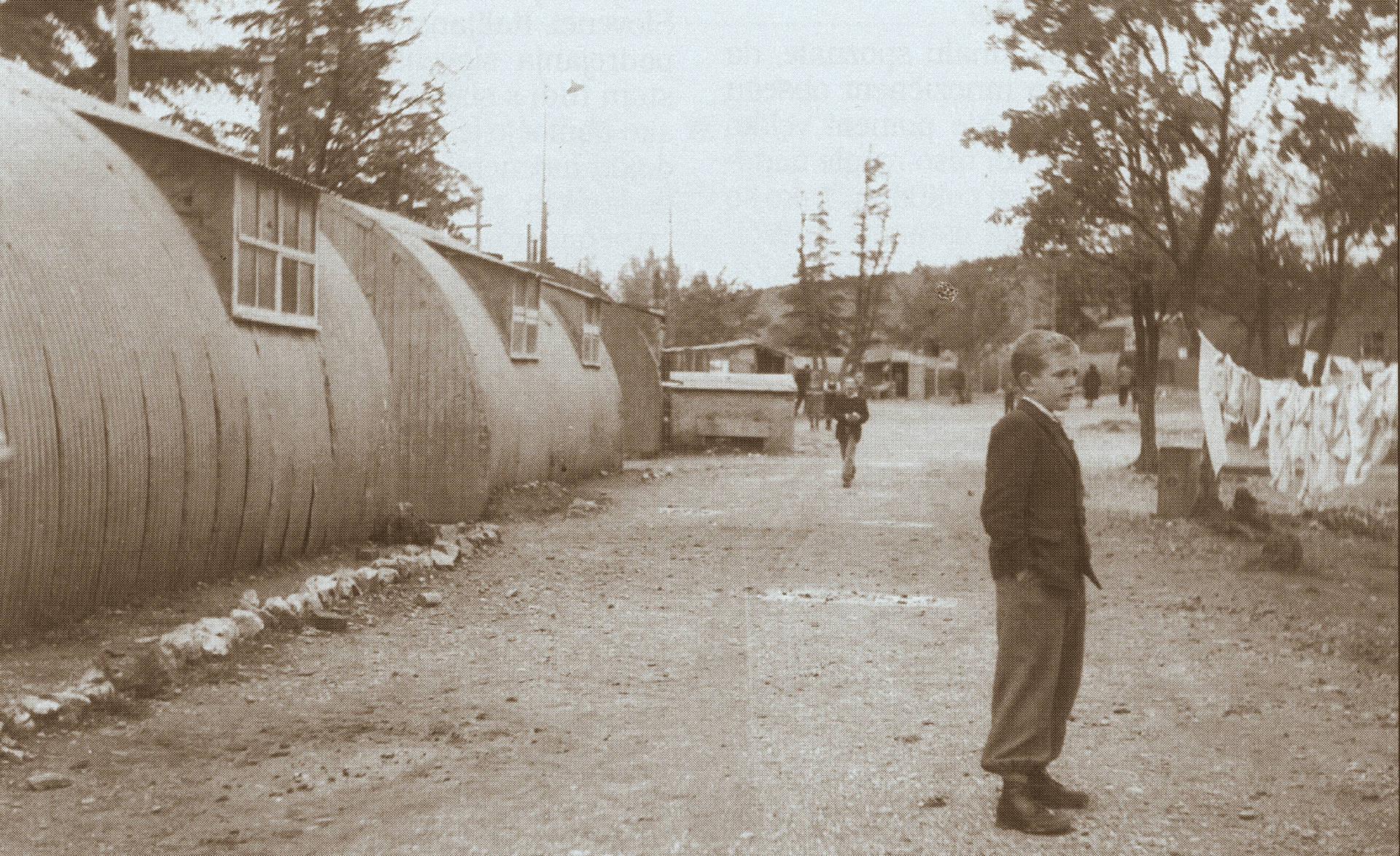

Opicina, 1951 – refugee camp.

Opicina, 1951 – refugee camp.