In the pre-Fascist period, the Italian political parties had guaranteed, via a resolution in parliament, the right of the various national minorities to cultivate their own language, culture and religion. With the advent of the first Fascist government, all this changed, since the very existence of national minorities was incompatible with Fascist doctrine. The Fascist policy of denationalisation was based on the denial of the existence of other nationalities within the borders of Italy, which in any case had been artificially created by the former foreign rulers of the territory. The Fascists thus used legal means to erase the outward appearance of the existence of a national minority. The leaders of the minority – members of the middle classes and the intelligentsia – were dispersed. The only exception was the clergy, which from then on appeared to be the only serious obstacle to assimilation. Beginning in 1931, a policy of colonisation was put into practice, with the aim of completing the process of Italianisation. The Fascists exploited the poverty of the Slav peasants and drove them to destitution.

Fascist Italy implemented its policy of denationalisation through the press, schools, social institutions, trade unions and political organisations.

The first ordinance regarding “suspect and dangerous persons” was issued in November 1918. While the territory was still under military administration, around a thousand individuals from the Julian March were interned in Sardinia and other regions, among them party leaders, teachers, lawyers and priests.

The first ordinance regarding “suspect and dangerous persons” was issued in November 1918. While the territory was still under military administration, around a thousand individuals from the Julian March were interned in Sardinia and other regions, among them party leaders, teachers, lawyers and priests.

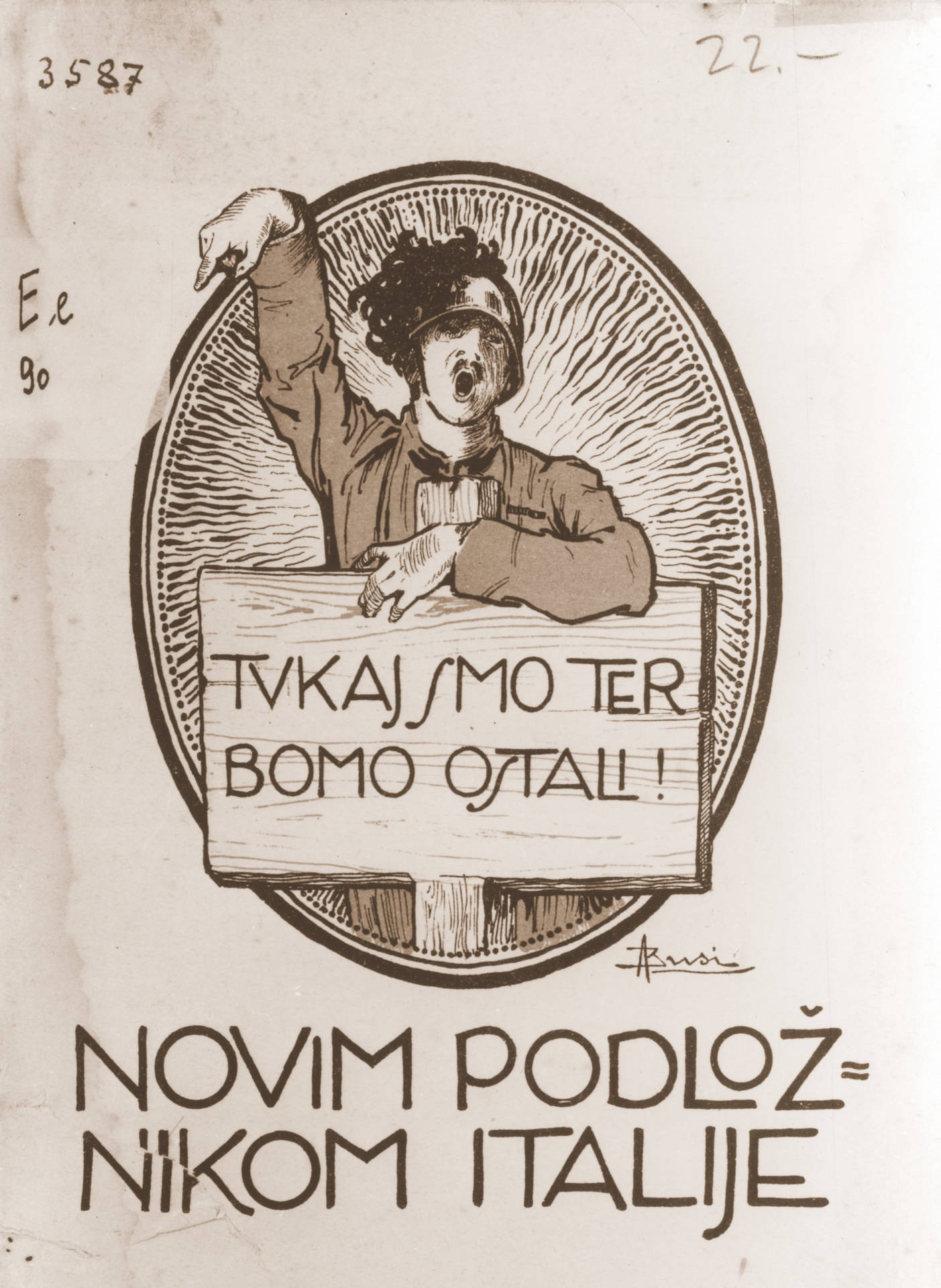

Front cover of booklet by Francesco Babudri.

Front cover of booklet by Francesco Babudri.

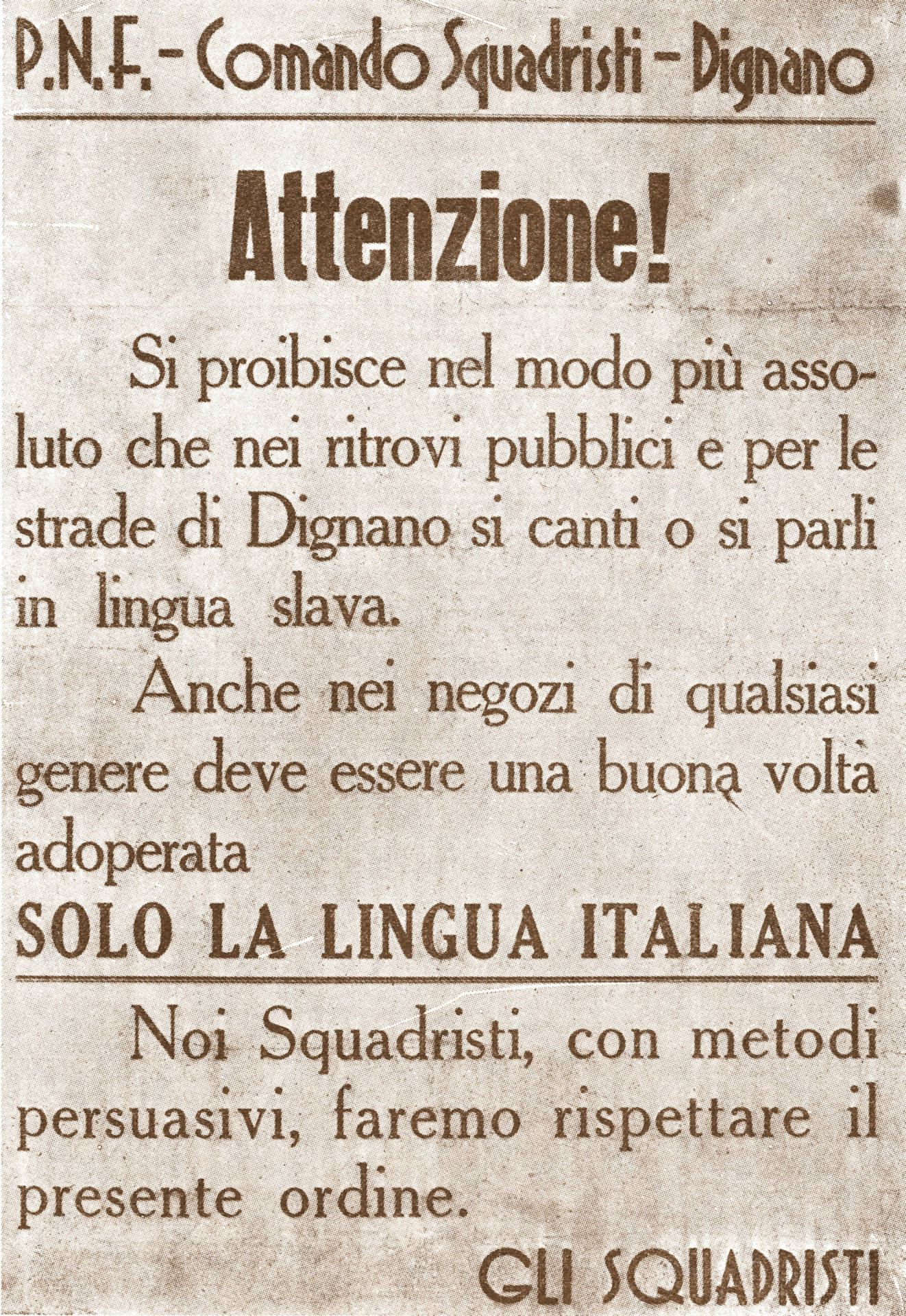

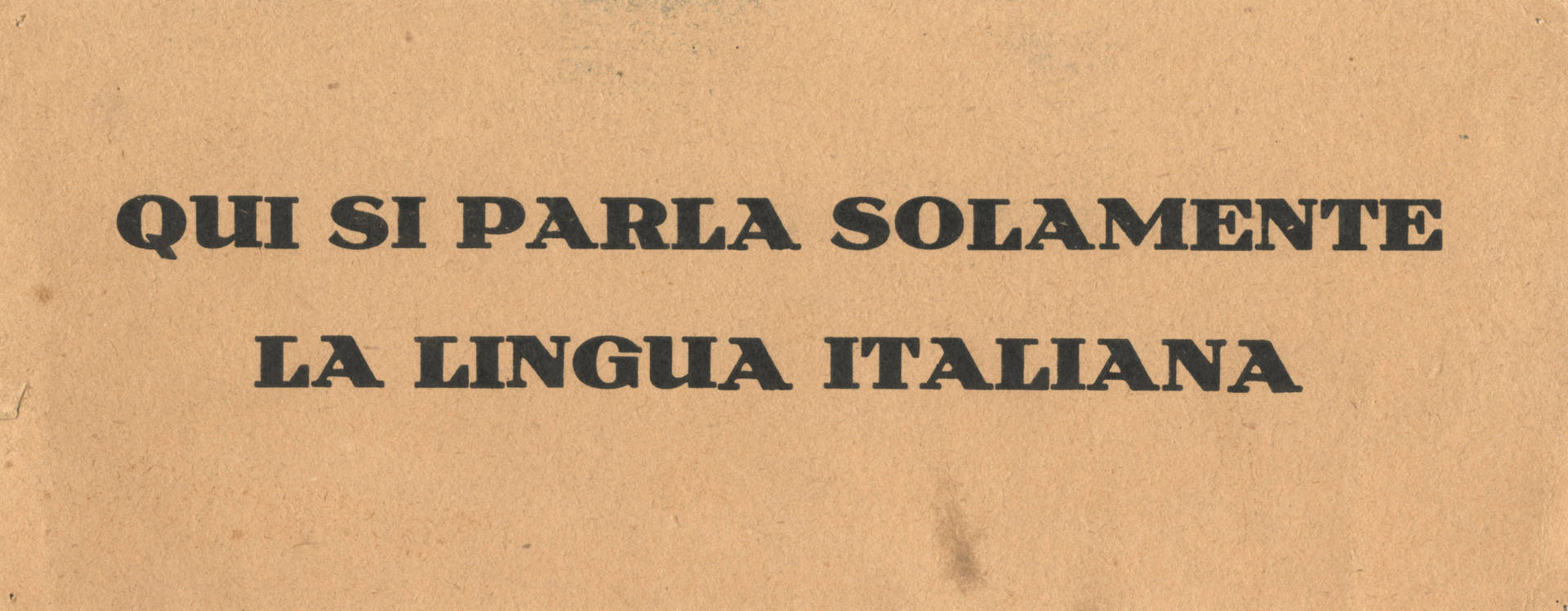

Fascist poster prohibiting the use of lingua slava (Slavic language) in public.

Fascist poster prohibiting the use of lingua slava (Slavic language) in public.

Dissolved 11 September 1927.

Dissolved 11 September 1927.

Dissolved 30 September 1927.

Dissolved 30 September 1927.

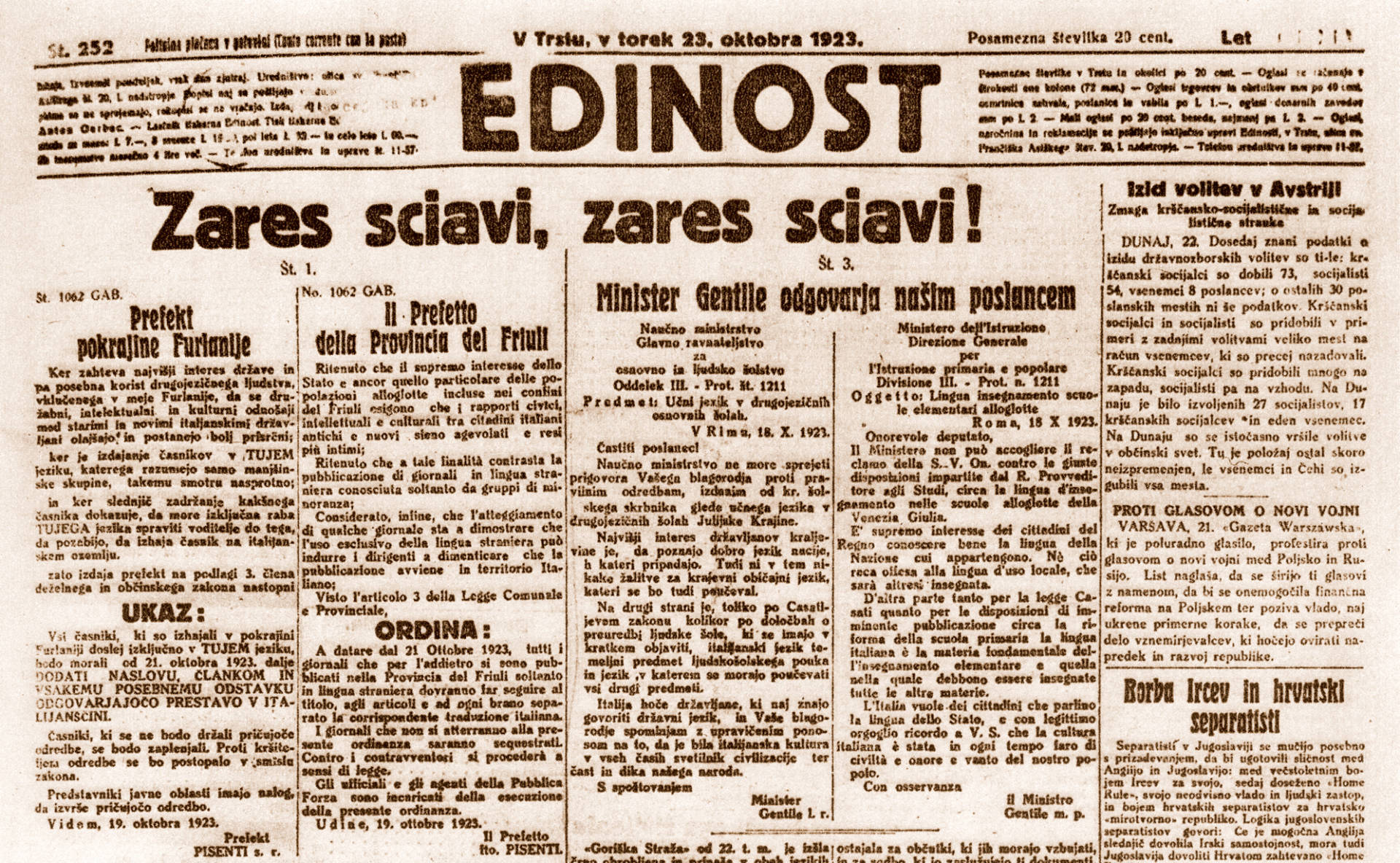

In October 1923 the prefect of Trieste issued an ordinance stating that all newspapers had to be published with an Italian translation.

In October 1923 the prefect of Trieste issued an ordinance stating that all newspapers had to be published with an Italian translation.

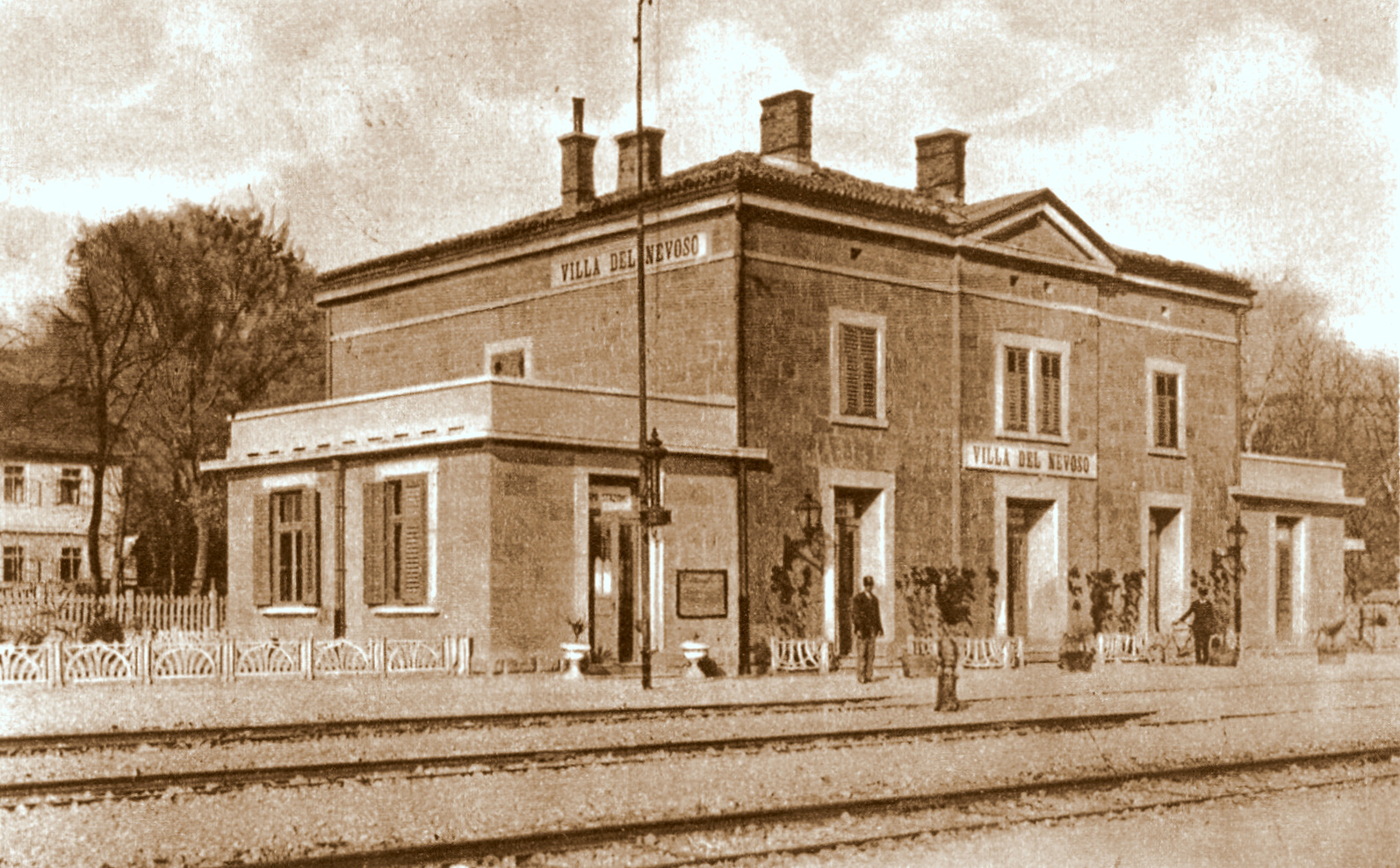

Ilirska Bistrica – railway station. The comune of Villa del Nevoso was created by merging the Trnovo and Bistrica municipalities in late 1927.

Ilirska Bistrica – railway station. The comune of Villa del Nevoso was created by merging the Trnovo and Bistrica municipalities in late 1927.

Abolished September 1928.

Abolished September 1928.

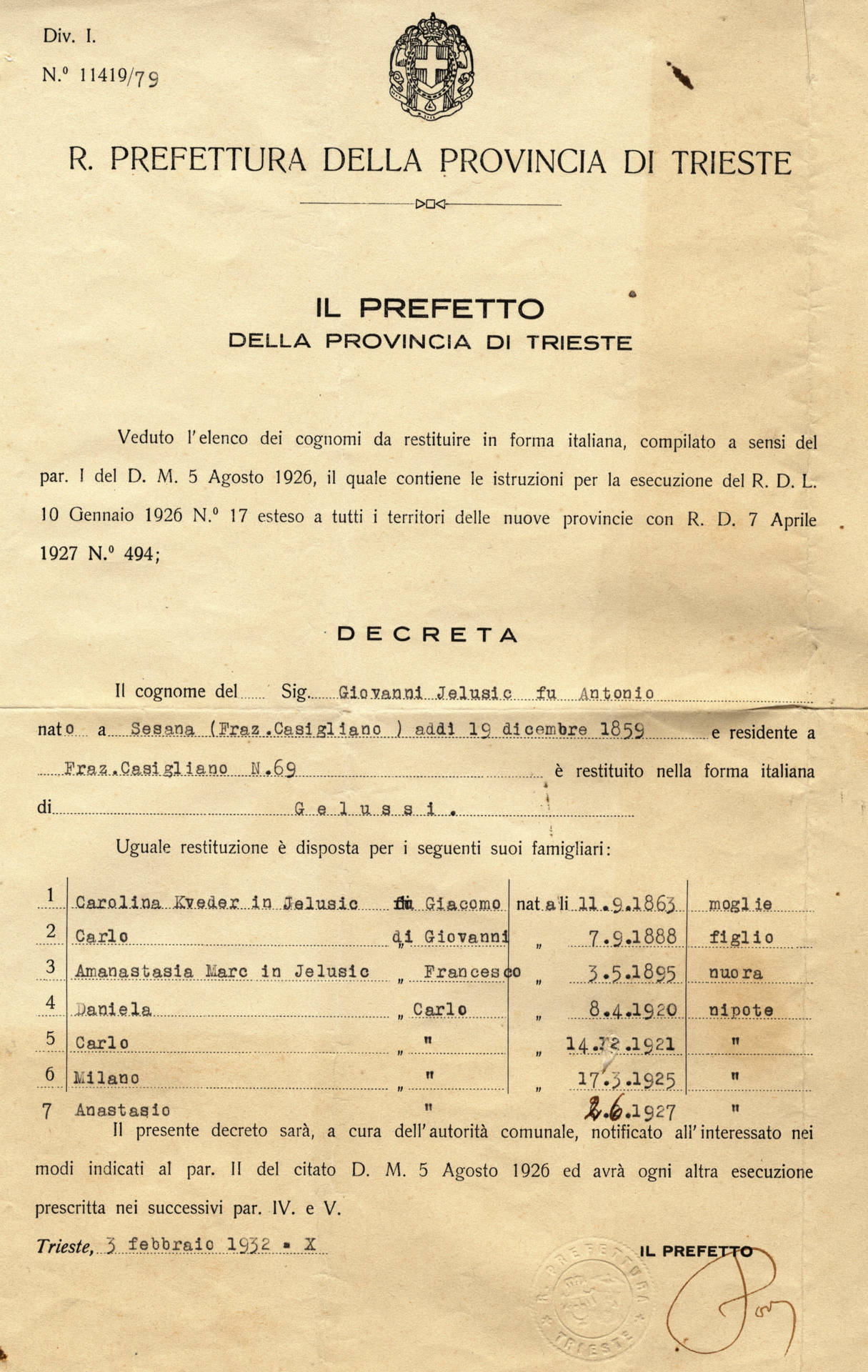

In January 1926 a law was passed on the Italianisation of surnames or, as the law put it, on the “restoration of the surname to its original form”. A further law adopted in March 1929 regulated the changing of first names, while from July 1939 people were prohibited from giving their children “foreign” names.

In January 1926 a law was passed on the Italianisation of surnames or, as the law put it, on the “restoration of the surname to its original form”. A further law adopted in March 1929 regulated the changing of first names, while from July 1939 people were prohibited from giving their children “foreign” names.

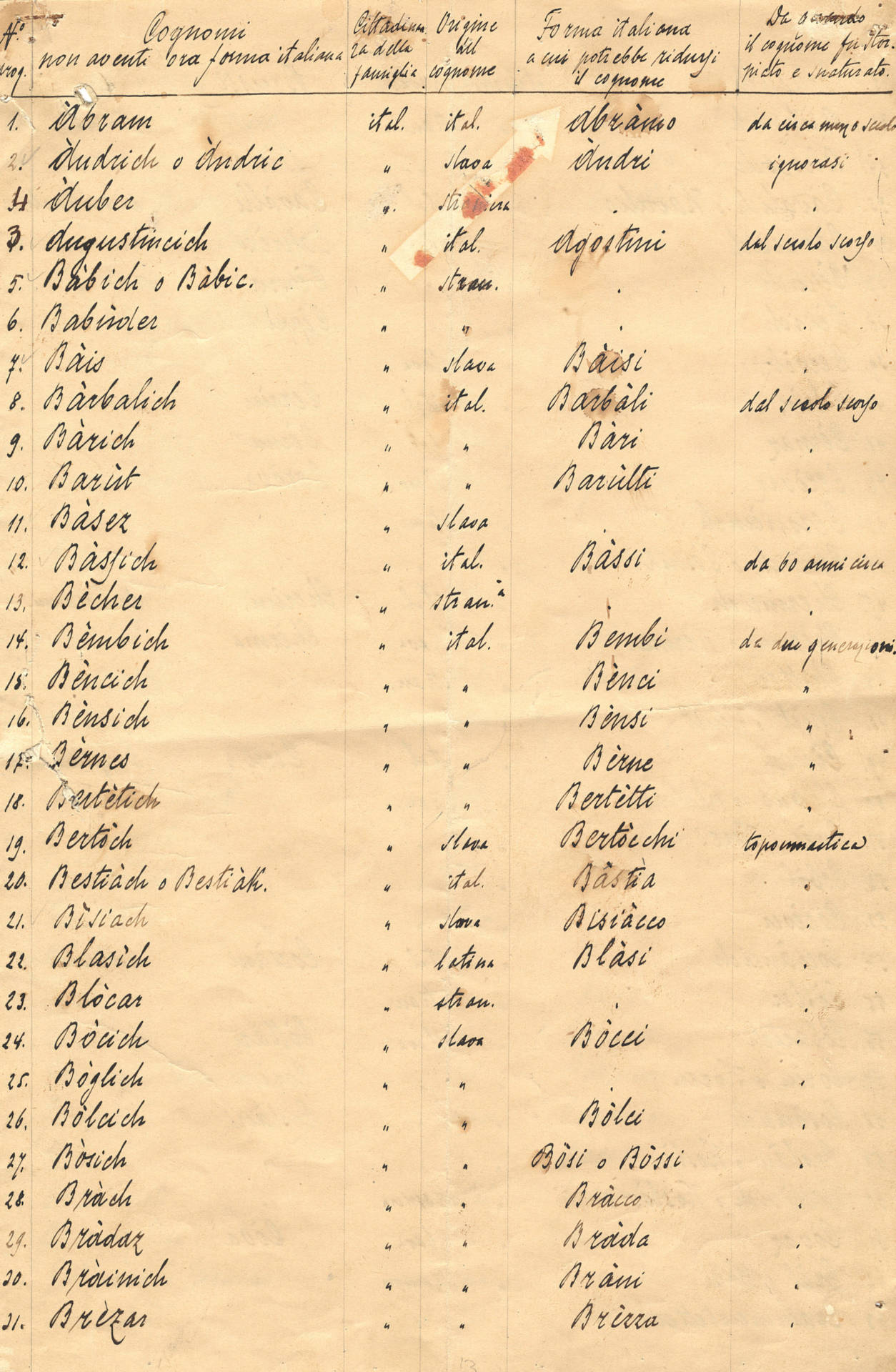

First page of a list of surnames needing to be Italianised. The last column states when the surname lost its Italian form.

First page of a list of surnames needing to be Italianised. The last column states when the surname lost its Italian form.

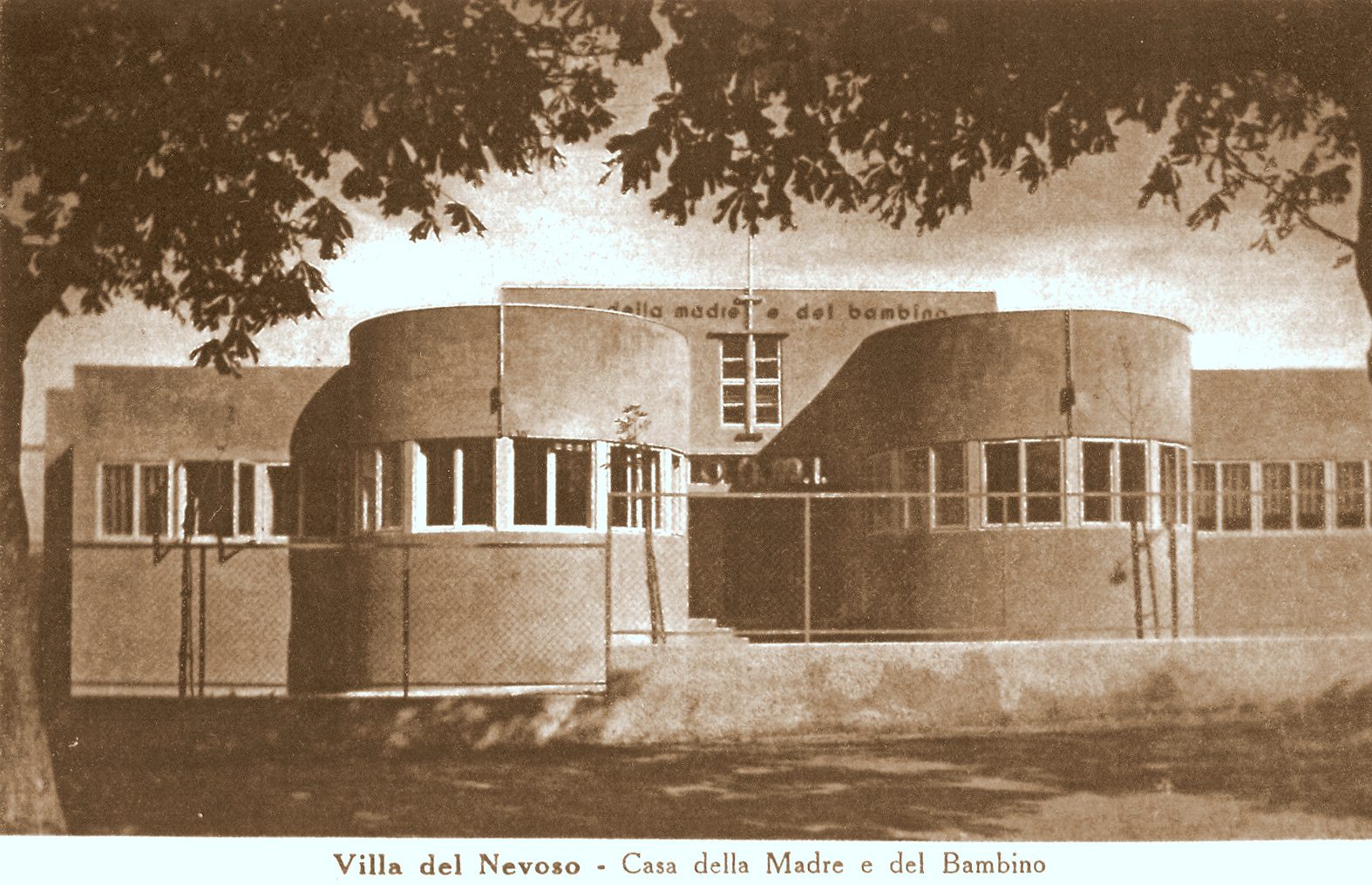

Maternity home in Ilirska Bistrica. Assimilation was also practised by welfare organisations such as Opera nazionale maternità e infanzia, Lega Nazionale and its successor ONAIR and Ente Opere Assistenziali.

Maternity home in Ilirska Bistrica. Assimilation was also practised by welfare organisations such as Opera nazionale maternità e infanzia, Lega Nazionale and its successor ONAIR and Ente Opere Assistenziali.

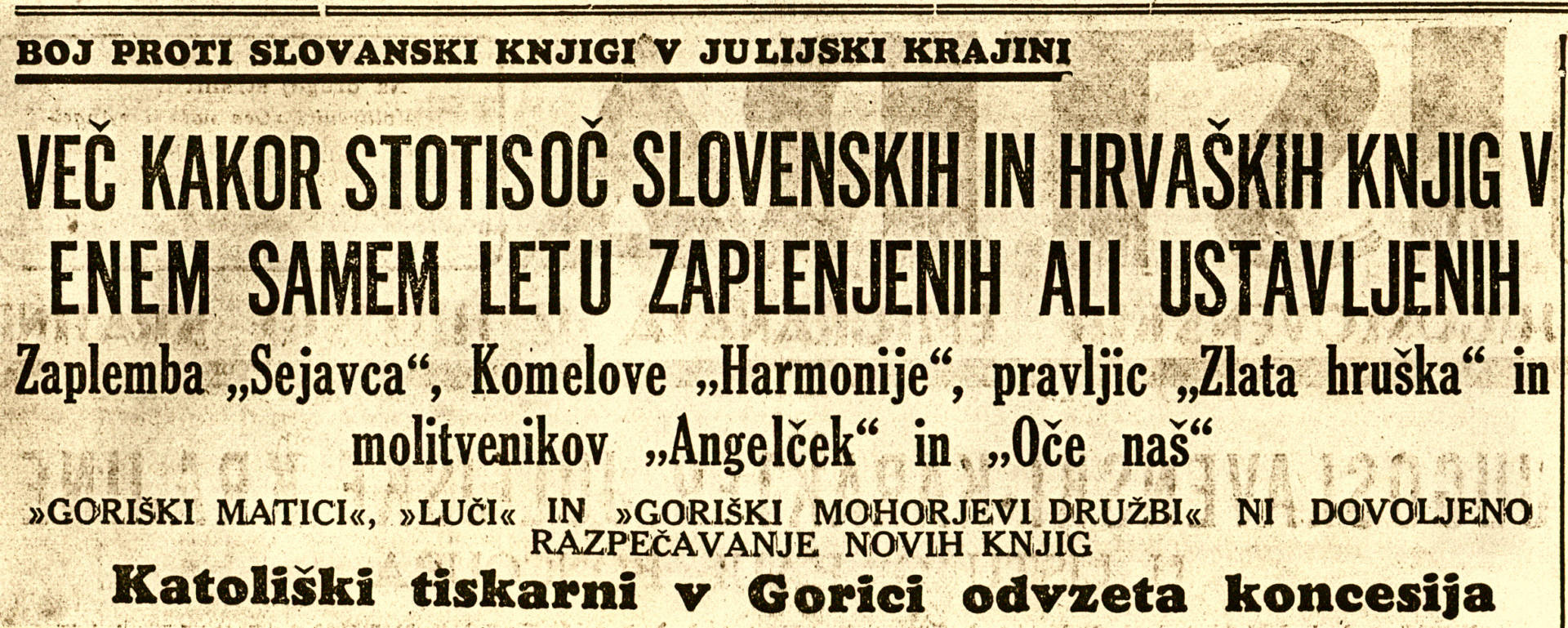

Serious criticism of the Fascist denationalisation policy only appeared in the emigré press.

Serious criticism of the Fascist denationalisation policy only appeared in the emigré press.

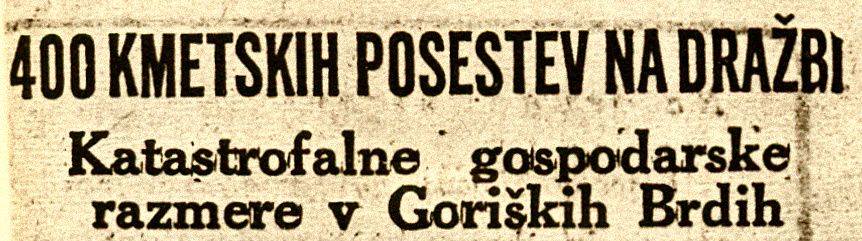

In 1931 the Ente per la rinascita agraria delle Tre Venezie (“Agency for the Agrarian Revival of the Triveneto”) was created to oversee the implementation of the colonisation project. In the period 1929–1934 a serious economic crisis plunged the rural population into poverty. Even individual cooperatives, loan societies and savings banks, which had previously helped farmers hold onto their property, went into gradual liquidation. Poverty-stricken farmers went abroad to seek work and their farms were bought up by Italian newcomers.

In 1931 the Ente per la rinascita agraria delle Tre Venezie (“Agency for the Agrarian Revival of the Triveneto”) was created to oversee the implementation of the colonisation project. In the period 1929–1934 a serious economic crisis plunged the rural population into poverty. Even individual cooperatives, loan societies and savings banks, which had previously helped farmers hold onto their property, went into gradual liquidation. Poverty-stricken farmers went abroad to seek work and their farms were bought up by Italian newcomers.

In 1931 the Ente per la rinascita agraria delle Tre Venezie (“Agency for the Agrarian Revival of the Triveneto”) was created to oversee the implementation of the colonisation project. In the period 1929–1934 a serious economic crisis plunged the rural population into poverty. Even individual cooperatives, loan societies and savings banks, which had previously helped farmers hold onto their property, went into gradual liquidation. Poverty-stricken farmers went abroad to seek work and their farms were bought up by Italian newcomers.

In 1931 the Ente per la rinascita agraria delle Tre Venezie (“Agency for the Agrarian Revival of the Triveneto”) was created to oversee the implementation of the colonisation project. In the period 1929–1934 a serious economic crisis plunged the rural population into poverty. Even individual cooperatives, loan societies and savings banks, which had previously helped farmers hold onto their property, went into gradual liquidation. Poverty-stricken farmers went abroad to seek work and their farms were bought up by Italian newcomers.

Emigrants waiting in Trieste for a ship to take them to New York. The photograph is from before the First World War.

Emigrants waiting in Trieste for a ship to take them to New York. The photograph is from before the First World War.